Are the financially deluded having conversations with the financially excluded? What will they talk about then...?

Barry Marlow outlines the case for overcoming the financial delusion which has persisted in UK social housing.

Barry Marlow outlines the case for overcoming the financial delusion which has persisted in UK social housing.

Financial Inclusion or Financial Delusion in Social Housing?

Would you pay an invisible bill? You know, a request for your funds and you don’t really know how much for? Of course not.

Payday lenders have attracted much bile in the housing press and the attention of the UK Government recently for their Continuous Payment Requests that limpet themselves to bank accounts and draw down funds even when the loanee isn’t looking, or expecting it.

Yet social housing also participates in requesting and chasing funds from customers which they know little about. The rent. If you, dear social landlord, went outside right now and asked 20 of your tenants how much their rent is, how many could tell you? Less than 50% is the answer, and here’s why…

‘Legalised Laundering’..?

About a generation ago social housing in the UK decided to exclude many of its tenants from the responsibility of paying rent. The social landlord decided instead that the balance sheet was far better if around 60% of revenue income was pretty much guaranteed. To achieve this, local authority housing benefit departments were sub-contracted to collect the rent from the taxpayer and pay it direct to the landlord without the tenants knowing. Under the guise of financial inclusion, to maximise how this worked, social housing staff were also encouraged to ‘verify’ housing benefit claims on behalf of their tenants.

This ‘legalised laundering’ produced about 60% risk free income that finance directors could happily sit back and forget about while it paid to fund improvements, repairs, new homes, mergers, and ancillary ‘housing plus’ activities such as community cohesion, employment and training, and ( most ironically of all) financial inclusion work.

The problem with this fantastic business model was the way it excluded the tenant from the basic responsibility of tenure – paying for the product and knowing what it cost.

Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is about knowing about finances. How can you include in that the majority who believe (and it is a belief) they ‘don’t pay rent’ – even if the tenancy agreement is quite explicit and doesn’t mention housing benefit as a joint tenant?

How on earth have inclusive and responsible landlords allowed this to happen?

Benefit calculators which many arrears and financial inclusion staff across social housing use to advise tenants on their potential benefit income to help pay their rent, are a brilliant innovation – trouble is, the first question is how much the rent is. Rent statements are tardy and mostly ill-timed. Rent increase letters to many tenants are meaningless. Rent arrears chase letters only confuse and often border the ridiculous. They are addressed to the excluded.

I often talk with people in arrears as part of my work. Recently I was carrying out some research into the creation of an incentive and reward programme for a housing association and spoke with some tenants. No, they don’t know how much the rent is. All of them were in rent arrears and a third could only guess at the level of their indebtedness. Yes, I know, these people are ‘feckless and financially irresponsible’. I read rent arrears letters and it’s pretty clear where the blame lies, (takes tongue from cheek…)

Connecting Rent to Reward

My friend Peter Hall wrote a brilliant article almost a year ago that introduced the concept of social landlords taking another look at incentive and reward programmes.

Peter’s theme was the different marketplace to that which confronted Dr Tom Manion in 1998 with Gold Service.

For example, recent work Peter and I did reveals a housing association with 6,000 homes exposed to the challenge under universal credit of needing to collect, or be paid, £15 million per year that at present is guaranteed. That’s a helluva business shift. Around £15 million that the payee is currently blissfully unaware of. It’s invisible. Too many social landlords are equally blissfully complacent.

Maybe connecting rent to reward is the business way forward. Most other commercial companies see the benefits and the inclusiveness in this approach. People see that they get something for something. Both the ‘somethings’ have a value and an incentive. The invisible has a worth.

I am pleased to be associated with Peter on the CIH Consultancy Working Together™ project Influencing Customer Behaviour this year. This project will explore the context and business planning of incentive and reward programmes.

A Wake Up call for Financial Delusion

The new – romantic era ended when Duran Duran split up. The remaining romantics in social housing who dream of golden days of guaranteed income need to realise the pragmatics and realities of the new marketplace. And I’m afraid that includes tenants and payday lenders. The customers’ world has moved on.

In my training seminars, we often talk about goals and ambitions – a visible place where we would like to be. In social housing, when I talk with tenants their main ambition is to have the peace of mind to allow them to make more informed, better and rational decisions. Or, as we may wish to call it, financial responsibility.

Like you, I wouldn’t pay an invisible bill. I’m not that deluded. Financial inclusion starts with visibility and responsibility.

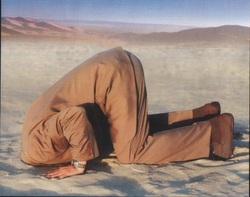

Many social landlords need to look in the mirror before leaving home.

Would you pay an invisible bill? You know, a request for your funds and you don’t really know how much for? Of course not.

Payday lenders have attracted much bile in the housing press and the attention of the UK Government recently for their Continuous Payment Requests that limpet themselves to bank accounts and draw down funds even when the loanee isn’t looking, or expecting it.

Yet social housing also participates in requesting and chasing funds from customers which they know little about. The rent. If you, dear social landlord, went outside right now and asked 20 of your tenants how much their rent is, how many could tell you? Less than 50% is the answer, and here’s why…

‘Legalised Laundering’..?

About a generation ago social housing in the UK decided to exclude many of its tenants from the responsibility of paying rent. The social landlord decided instead that the balance sheet was far better if around 60% of revenue income was pretty much guaranteed. To achieve this, local authority housing benefit departments were sub-contracted to collect the rent from the taxpayer and pay it direct to the landlord without the tenants knowing. Under the guise of financial inclusion, to maximise how this worked, social housing staff were also encouraged to ‘verify’ housing benefit claims on behalf of their tenants.

This ‘legalised laundering’ produced about 60% risk free income that finance directors could happily sit back and forget about while it paid to fund improvements, repairs, new homes, mergers, and ancillary ‘housing plus’ activities such as community cohesion, employment and training, and ( most ironically of all) financial inclusion work.

The problem with this fantastic business model was the way it excluded the tenant from the basic responsibility of tenure – paying for the product and knowing what it cost.

Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is about knowing about finances. How can you include in that the majority who believe (and it is a belief) they ‘don’t pay rent’ – even if the tenancy agreement is quite explicit and doesn’t mention housing benefit as a joint tenant?

How on earth have inclusive and responsible landlords allowed this to happen?

Benefit calculators which many arrears and financial inclusion staff across social housing use to advise tenants on their potential benefit income to help pay their rent, are a brilliant innovation – trouble is, the first question is how much the rent is. Rent statements are tardy and mostly ill-timed. Rent increase letters to many tenants are meaningless. Rent arrears chase letters only confuse and often border the ridiculous. They are addressed to the excluded.

I often talk with people in arrears as part of my work. Recently I was carrying out some research into the creation of an incentive and reward programme for a housing association and spoke with some tenants. No, they don’t know how much the rent is. All of them were in rent arrears and a third could only guess at the level of their indebtedness. Yes, I know, these people are ‘feckless and financially irresponsible’. I read rent arrears letters and it’s pretty clear where the blame lies, (takes tongue from cheek…)

Connecting Rent to Reward

My friend Peter Hall wrote a brilliant article almost a year ago that introduced the concept of social landlords taking another look at incentive and reward programmes.

Peter’s theme was the different marketplace to that which confronted Dr Tom Manion in 1998 with Gold Service.

For example, recent work Peter and I did reveals a housing association with 6,000 homes exposed to the challenge under universal credit of needing to collect, or be paid, £15 million per year that at present is guaranteed. That’s a helluva business shift. Around £15 million that the payee is currently blissfully unaware of. It’s invisible. Too many social landlords are equally blissfully complacent.

Maybe connecting rent to reward is the business way forward. Most other commercial companies see the benefits and the inclusiveness in this approach. People see that they get something for something. Both the ‘somethings’ have a value and an incentive. The invisible has a worth.

I am pleased to be associated with Peter on the CIH Consultancy Working Together™ project Influencing Customer Behaviour this year. This project will explore the context and business planning of incentive and reward programmes.

A Wake Up call for Financial Delusion

The new – romantic era ended when Duran Duran split up. The remaining romantics in social housing who dream of golden days of guaranteed income need to realise the pragmatics and realities of the new marketplace. And I’m afraid that includes tenants and payday lenders. The customers’ world has moved on.

In my training seminars, we often talk about goals and ambitions – a visible place where we would like to be. In social housing, when I talk with tenants their main ambition is to have the peace of mind to allow them to make more informed, better and rational decisions. Or, as we may wish to call it, financial responsibility.

Like you, I wouldn’t pay an invisible bill. I’m not that deluded. Financial inclusion starts with visibility and responsibility.

Many social landlords need to look in the mirror before leaving home.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed