Peter Hall (@PHHSl) reflects on key questions discussed in a session at #housingcamp held at Thames Valley HA's offices on 18th May, with some useful history thrown in for good measure!

I spent last Saturday discussing the future and challenges for the #ukhousing sector with some great people at the fantastic #housingcamp conference and led a session on whether the social housing sector needs a new positive message.

I began the session reflecting on the fact that despite what David Orr recently described as a ‘pernicious but persuasive narrative’ about welfare, a JRF report published last week confirmed the public increasingly believe that individuals live on benefits as a result of their own laziness rather than an unfair society in which they cannot find work - and posing the question: does social housing need a new message, or does it just need to recognise its limitations?

We didn’t come to any firm conclusions at the session but had a great discussion. This article is based on the discussions, but I’m also suggesting that part of the answer to the question is the sector recognising its place, and then developing a simple message and stories about the impact it has on individual’s and their families life chances. Beyond that is either too ambitious or too political.

History Repeating Itself?

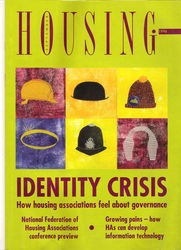

While I was lubricating the cogs of my mind on Saturday, my wife took the opportunity to spring clean the garage, so I spent the following morning reflecting on some history from the sector – which was very cathartic as it turns out. Amongst old University papers & issues of Inside Housing and Housing magazine which she’d earmarked for me to take to the tip, I found some historical gems relating to the session I led. Behold below, the ‘housing’ headlines from 1994.

I began the session reflecting on the fact that despite what David Orr recently described as a ‘pernicious but persuasive narrative’ about welfare, a JRF report published last week confirmed the public increasingly believe that individuals live on benefits as a result of their own laziness rather than an unfair society in which they cannot find work - and posing the question: does social housing need a new message, or does it just need to recognise its limitations?

We didn’t come to any firm conclusions at the session but had a great discussion. This article is based on the discussions, but I’m also suggesting that part of the answer to the question is the sector recognising its place, and then developing a simple message and stories about the impact it has on individual’s and their families life chances. Beyond that is either too ambitious or too political.

History Repeating Itself?

While I was lubricating the cogs of my mind on Saturday, my wife took the opportunity to spring clean the garage, so I spent the following morning reflecting on some history from the sector – which was very cathartic as it turns out. Amongst old University papers & issues of Inside Housing and Housing magazine which she’d earmarked for me to take to the tip, I found some historical gems relating to the session I led. Behold below, the ‘housing’ headlines from 1994.

The same issues, the same ‘crises’ and the same challenges for the sector in adapting to a new operating environment? And some interesting commentary from Julian Ashby - now Chair of the HCA Regulatory Committee. Yet the sector survived & continued to grow - delivering 1/4m new homes and with almost 1/2m stock transferred to new Housing Associations between 1996/97 and 2008/09. It branched out into shared ownership, spent £bns on decent homes programmes in the noughties, attracted £bn’s of private finance, and generated £1.8bn of surpluses in the ‘RP’ sector in the last financial year. The sector has a great track record of responding to and adapting to change.

Perception is 9/10’s of reality

The current ‘crises’ facing the sector have similar themes of reductions in grant funding, recession, the availability of finance and ‘diversification’ for landlords as the early 90’s – only this time compounded by the additional factor of welfare reform. That welfare reform and the bedroom tax are now a reality speaks louder than any words can about the sector’s inability to influence government or public opinion. Even amidst the street protests organised by tenants themselves and high profile media interest in the run up to this April’s launch, public support for welfare reform and the bedroom tax remained high.

As Thom Bartley put it recently, the housing sector should have a strong powerful voice that influences business and social policy, but that voice is currently ‘like a whingy little field mouse moaning away and being ignored whenever something happens that we don’t like’

But this lack of voice isn’t just about too much navel gazing within the sector or a lack of communication and integration with businesses and groups in the wider world.

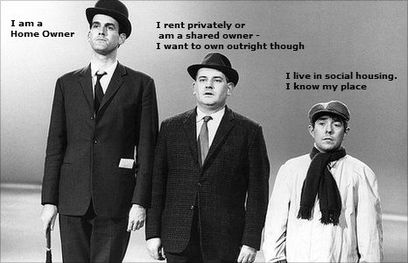

The harsh reality is that while social housing is rationed, targeted at those most ‘in need’, and subsidised with taxpayers’ money (both in initial building and running costs via Housing Benefit, Supporting People or Universal Credit), it will be perceived as a safety net and not the tenure of first choice. It will also be subject to a whole host of scrutiny and negative press about fraud, fecklessness and notions of achieving better value for taxpayers.

While it remains rationed, and unlike in some Northern European countries or even Singapore (as outlined by one of the delegates @ #housingcamp) it will never be a ‘neutral’ tenure. Even In the ‘golden age’ post war years when council housing was genuinely for the masses and housing associations catered mainly for single and professional couples, home ownership was a growing aspiration for many (realised under RTB) and will continue to be that way as long as homes are treated as appreciating assets rather than utilities, house prices are a barometer of economic health, and mortgages are available to the general public.

Despite the growth in numbers, costs and insecurity of private renting, The English Household Survey consistently shows higher levels of satisfaction amongst private tenants with their overall home and neighbourhood than evident in the social housing sector too.

So the sector needs to appreciate that home ownership and private renting are the tenures of choice and will always have a louder voice and influence over the government and the general population as a result. Social housing’s place is, and perhaps always will be, the tenure of least choice. Recognise that, and move on.

Responding to Changing Attitudes

The response of many in the sector of late to spending cuts has been to increase direct spending on welfare or money advice services. Others are following ( in part, if not in full) Tom Manion’s lead and offering services on a something for something basis – either via rewards schemes such as Irwell Valley’s or behavioural requirements such as those recently developed at Yarlington Housing.

But the JRF report published last week is one of many which have confirmed a hardening of public attitudes to welfare which also predate the current age of austerity. This article in the Guardian a few months back outlined how Generation Y are year on year becoming more inclined to individualist views on welfare and less supportive of state provision, and opinion polls consistently show high support for vulnerable people being given a hand up rather than a hand out.

If a hand up means the most basic of the sector’s aims of providing housing, that’s probably what the general public think the sector’s role is too. Yet the sector as a whole currently spends in the region of £1bn a year on non housing activities (such as community development, employment & training, benefits advice and resident involvement) instead of new homes, and many are actually closing up shop to new development. This at a time when, as has just been revealed, it is costing £2bn a year to place families in B&B and temporary accommodation across the country.

So it is perhaps a time to ask some fundamental questions about the sector’s role in and the value for money of additional services provided aimed at the welfare of tenants rather than building new homes. How can the benefits and costs of spending on welfare be promoted and justified when:

1. Such activity is rarely if ever high on the agenda of existing or potential tenants in any opinion surveys. The 2008 TSA ‘National Conversation’ findings mirrored all of the status and star survey findings I’ve come across in that existing and potential tenants felt the most important services from a landlord were repairs and maintenance, health and safety for tenants, keeping them informed and dealing with complaints. The findings were also that while ‘ additional services were regarded as positive by tenants… there was a strong feeling that landlords should get the basics right first. The greatest concern expressed by tenants was in relation to how additional services would be paid for and whether they would benefit directly”

2. It is hard to put a value on the benefits for individual tenants or their wider communities. Social Return on Investment methodologies and HACT are doing some good work at attempting to quantify the outcomes and benefits from non housing spend, but they remain couched in a language which many in the profession don’t understand and aren’t signed up to - let alone tenants or the general public. Measuring social value has also been piloted in Australia and public attitudes as well as government approaches to social housing there have not changed.

3. We’re on the cusp of fundamental shift in the relationship between landlords and tenants not seen since the 1980’s. The direct payment relationship which will develop in the coming years via Universal Credit and benefit caps will inevitably lead to a greater awareness for tenants of their of outgoings – especially the 60%+ who currently rely on benefits to cover their rents – and ultimately the level of their rent and what it is spent on.

Philanthropic support and the charitable basis of housing isn’t new, and effective work on community development has a track record of helping to create sustainable neighbourhoods which contribute to improved environments for tenants and their families. People like Phillip Blond may be calling for the sector to do exciting and radical things like setting up free schools, or bidding to help deliver the new Work Programme, but the sector needs to address these questions and demonstrate how any spend on additional services is delivering improved life chances for their tenants and families to gain support across the wider public and any traction with government.

Challenging the Complacent Consensus

The 2011 Government Housing Strategy set out their aim to ‘challenge the established complacent consensus around social housing, which has plainly contributed to an inefficient system’ through ‘a more proactive approach to value for money regulation to encourage increased focus on operating costs and using assets effectively’ to ‘help free up financial capacity for investment in new and existing stock’.

All the key changes that have been introduced in the last couple of years have been imposed on the sector. Affordable rents, fixed term tenancies, the bedroom tax, making tenancy fraud and squatting a criminal offence, the new regulatory standards, pay to stay for high income tenants, the enhanced right to buy etc. My instinct is that if tenants were asked for their views, most would agree with most of them. Yet the sector’s representatives and press have had nothing to offer in the main to these other than negative ‘won’t work’ or, too much risk’ or ‘the end is nigh for social housing’ responses. A review of the #ukhousing twitter hash tag at times seems like a collation of all the bad news from across the sector in one place, and a competition to see who can predict the most doom and gloom.

Is it a coincidence that George Osborne stated in response to this March’s budget that more social housing isn’t an answer to the housing crisis?

Where is the dynamism and proactive approach to all of these issues in the sector? There are some who are genuinely at the leading edge of diversifying into private rent and outright sale to subsidise their social housing, and every week there’s some new ground breaking below spread basis points bond deal securing £bn’s of loan finance.

Almost half of the 2012 Sunday Times 100 best not-for-profit organisations to work for were social housing organisations or homeless charities, and seven of the top 10 were social landlords too. Social housing certainly isn’t therefore the employment of last resort, but nobody is stepping up to break the mould on social housing being the tenure of last resort.

At #housingcamp we discussed how flexible tenure could be part of the solution, and how measures such as fixed term tenancies and pay to stay are potentially paving the way for it to become a reality. Imagine the difference it might make to the image of social housing if tenants could move up or down through tenures in the same property throughout their lifetime as circumstances dictate, and if some of the sale or additional rent proceeds were reinvested into open market properties for rent in genuinely mixed tenure neighbourhoods, rather than monolithic estates or little enclaves of rented housing tucked away at the back of a private development? Or even if qualifying tenants were given an equity share in their home. Neither of these are new ideas, but they have the potential to deliver genuine choices and a stake in social housing for the whole of the population.

A New Message then, or a different one?

If there was a clear message about social housing it would be great. Alastair Campbell suggested at the CIH SE Conference earlier this year that the sector needed to work on a simpler message focused on the future. ‘In Business for Neighbourhoods’ was a simple & successful phrase in the housing association sector, as is ‘Placehshapers’, but ask anyone outside the sector and they won’t know of or understand them, and ask anyone working for councils, and they might not either. As for the G15, most will think they’re government meetings which anti capitalists demonstrate against.

One thing’s for certain. Increasing the sector’s influence and changing public perceptions through statistics, moans or predictions of doom and gloom is about as likely as a long hot summer every year. As Thom Bartley also said recently. “Human stories and how policy and events affect the individual resonate in peoples psyches much more powerfully than stats and figures”

In its current form, the national press will always be able to demonise social housing. Having grown up on a council estate and worked in the sector for over 20 years, I know there are some fantastic stories to be told about how it provides better life chances and a platform for some to improve theirs. There are some equally mundane ones. The challenge for the sector is to harness those on a positive basis, but how to do it with such a variety of players and interests….?

Perception is 9/10’s of reality

The current ‘crises’ facing the sector have similar themes of reductions in grant funding, recession, the availability of finance and ‘diversification’ for landlords as the early 90’s – only this time compounded by the additional factor of welfare reform. That welfare reform and the bedroom tax are now a reality speaks louder than any words can about the sector’s inability to influence government or public opinion. Even amidst the street protests organised by tenants themselves and high profile media interest in the run up to this April’s launch, public support for welfare reform and the bedroom tax remained high.

As Thom Bartley put it recently, the housing sector should have a strong powerful voice that influences business and social policy, but that voice is currently ‘like a whingy little field mouse moaning away and being ignored whenever something happens that we don’t like’

But this lack of voice isn’t just about too much navel gazing within the sector or a lack of communication and integration with businesses and groups in the wider world.

The harsh reality is that while social housing is rationed, targeted at those most ‘in need’, and subsidised with taxpayers’ money (both in initial building and running costs via Housing Benefit, Supporting People or Universal Credit), it will be perceived as a safety net and not the tenure of first choice. It will also be subject to a whole host of scrutiny and negative press about fraud, fecklessness and notions of achieving better value for taxpayers.

While it remains rationed, and unlike in some Northern European countries or even Singapore (as outlined by one of the delegates @ #housingcamp) it will never be a ‘neutral’ tenure. Even In the ‘golden age’ post war years when council housing was genuinely for the masses and housing associations catered mainly for single and professional couples, home ownership was a growing aspiration for many (realised under RTB) and will continue to be that way as long as homes are treated as appreciating assets rather than utilities, house prices are a barometer of economic health, and mortgages are available to the general public.

Despite the growth in numbers, costs and insecurity of private renting, The English Household Survey consistently shows higher levels of satisfaction amongst private tenants with their overall home and neighbourhood than evident in the social housing sector too.

So the sector needs to appreciate that home ownership and private renting are the tenures of choice and will always have a louder voice and influence over the government and the general population as a result. Social housing’s place is, and perhaps always will be, the tenure of least choice. Recognise that, and move on.

Responding to Changing Attitudes

The response of many in the sector of late to spending cuts has been to increase direct spending on welfare or money advice services. Others are following ( in part, if not in full) Tom Manion’s lead and offering services on a something for something basis – either via rewards schemes such as Irwell Valley’s or behavioural requirements such as those recently developed at Yarlington Housing.

But the JRF report published last week is one of many which have confirmed a hardening of public attitudes to welfare which also predate the current age of austerity. This article in the Guardian a few months back outlined how Generation Y are year on year becoming more inclined to individualist views on welfare and less supportive of state provision, and opinion polls consistently show high support for vulnerable people being given a hand up rather than a hand out.

If a hand up means the most basic of the sector’s aims of providing housing, that’s probably what the general public think the sector’s role is too. Yet the sector as a whole currently spends in the region of £1bn a year on non housing activities (such as community development, employment & training, benefits advice and resident involvement) instead of new homes, and many are actually closing up shop to new development. This at a time when, as has just been revealed, it is costing £2bn a year to place families in B&B and temporary accommodation across the country.

So it is perhaps a time to ask some fundamental questions about the sector’s role in and the value for money of additional services provided aimed at the welfare of tenants rather than building new homes. How can the benefits and costs of spending on welfare be promoted and justified when:

1. Such activity is rarely if ever high on the agenda of existing or potential tenants in any opinion surveys. The 2008 TSA ‘National Conversation’ findings mirrored all of the status and star survey findings I’ve come across in that existing and potential tenants felt the most important services from a landlord were repairs and maintenance, health and safety for tenants, keeping them informed and dealing with complaints. The findings were also that while ‘ additional services were regarded as positive by tenants… there was a strong feeling that landlords should get the basics right first. The greatest concern expressed by tenants was in relation to how additional services would be paid for and whether they would benefit directly”

2. It is hard to put a value on the benefits for individual tenants or their wider communities. Social Return on Investment methodologies and HACT are doing some good work at attempting to quantify the outcomes and benefits from non housing spend, but they remain couched in a language which many in the profession don’t understand and aren’t signed up to - let alone tenants or the general public. Measuring social value has also been piloted in Australia and public attitudes as well as government approaches to social housing there have not changed.

3. We’re on the cusp of fundamental shift in the relationship between landlords and tenants not seen since the 1980’s. The direct payment relationship which will develop in the coming years via Universal Credit and benefit caps will inevitably lead to a greater awareness for tenants of their of outgoings – especially the 60%+ who currently rely on benefits to cover their rents – and ultimately the level of their rent and what it is spent on.

Philanthropic support and the charitable basis of housing isn’t new, and effective work on community development has a track record of helping to create sustainable neighbourhoods which contribute to improved environments for tenants and their families. People like Phillip Blond may be calling for the sector to do exciting and radical things like setting up free schools, or bidding to help deliver the new Work Programme, but the sector needs to address these questions and demonstrate how any spend on additional services is delivering improved life chances for their tenants and families to gain support across the wider public and any traction with government.

Challenging the Complacent Consensus

The 2011 Government Housing Strategy set out their aim to ‘challenge the established complacent consensus around social housing, which has plainly contributed to an inefficient system’ through ‘a more proactive approach to value for money regulation to encourage increased focus on operating costs and using assets effectively’ to ‘help free up financial capacity for investment in new and existing stock’.

All the key changes that have been introduced in the last couple of years have been imposed on the sector. Affordable rents, fixed term tenancies, the bedroom tax, making tenancy fraud and squatting a criminal offence, the new regulatory standards, pay to stay for high income tenants, the enhanced right to buy etc. My instinct is that if tenants were asked for their views, most would agree with most of them. Yet the sector’s representatives and press have had nothing to offer in the main to these other than negative ‘won’t work’ or, too much risk’ or ‘the end is nigh for social housing’ responses. A review of the #ukhousing twitter hash tag at times seems like a collation of all the bad news from across the sector in one place, and a competition to see who can predict the most doom and gloom.

Is it a coincidence that George Osborne stated in response to this March’s budget that more social housing isn’t an answer to the housing crisis?

Where is the dynamism and proactive approach to all of these issues in the sector? There are some who are genuinely at the leading edge of diversifying into private rent and outright sale to subsidise their social housing, and every week there’s some new ground breaking below spread basis points bond deal securing £bn’s of loan finance.

Almost half of the 2012 Sunday Times 100 best not-for-profit organisations to work for were social housing organisations or homeless charities, and seven of the top 10 were social landlords too. Social housing certainly isn’t therefore the employment of last resort, but nobody is stepping up to break the mould on social housing being the tenure of last resort.

At #housingcamp we discussed how flexible tenure could be part of the solution, and how measures such as fixed term tenancies and pay to stay are potentially paving the way for it to become a reality. Imagine the difference it might make to the image of social housing if tenants could move up or down through tenures in the same property throughout their lifetime as circumstances dictate, and if some of the sale or additional rent proceeds were reinvested into open market properties for rent in genuinely mixed tenure neighbourhoods, rather than monolithic estates or little enclaves of rented housing tucked away at the back of a private development? Or even if qualifying tenants were given an equity share in their home. Neither of these are new ideas, but they have the potential to deliver genuine choices and a stake in social housing for the whole of the population.

A New Message then, or a different one?

If there was a clear message about social housing it would be great. Alastair Campbell suggested at the CIH SE Conference earlier this year that the sector needed to work on a simpler message focused on the future. ‘In Business for Neighbourhoods’ was a simple & successful phrase in the housing association sector, as is ‘Placehshapers’, but ask anyone outside the sector and they won’t know of or understand them, and ask anyone working for councils, and they might not either. As for the G15, most will think they’re government meetings which anti capitalists demonstrate against.

One thing’s for certain. Increasing the sector’s influence and changing public perceptions through statistics, moans or predictions of doom and gloom is about as likely as a long hot summer every year. As Thom Bartley also said recently. “Human stories and how policy and events affect the individual resonate in peoples psyches much more powerfully than stats and figures”

In its current form, the national press will always be able to demonise social housing. Having grown up on a council estate and worked in the sector for over 20 years, I know there are some fantastic stories to be told about how it provides better life chances and a platform for some to improve theirs. There are some equally mundane ones. The challenge for the sector is to harness those on a positive basis, but how to do it with such a variety of players and interests….?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed